1646 Photo: Maarten Nauw

The phrase “Welcome to Europe” echoes like the opening line of the 2024 Eurovision Song Contest entry by the Dutch contestant, hinting at the universal yearning for travel and self-discovery. It celebrates the freedom to travel across borders, an achievement of the European Union amidst ongoing efforts for unity, solidarity, and freedom. The origin of the name Europa is believed to stem from Greek mythology, referring to the name of a Phoenician princess who was abducted by Zeus in the guise of a white bull. He was terribly in love with her. Alternatively, it may stem from the Greek roots eur- (wide) and -op (seeing) to form the phrase “wide-gazing”—having one’s eyes wide open with wonder or astonishment.

Europe is a mix of cultures and landscapes. Here, amidst various contexts and at different times, guest studios or art residencies, often organized by artists, have been created as spaces to explore ideas through working and living together; ways of making new art; new relations between creation and everyday life, and new organizational forms outside the rules of institutions or society. From field research at the fjords along the Danish coastline to writing your next film script in a quaint neighborhood cafe in a quiet Belgian town, artist-in-residence programs provide a way to immerse oneself in new environments and experiences.

Grassroots movements have significantly influenced the landscape of artist residencies in Europe. Since the 1900s, artists have been engaged in bottom-up initiatives, defining their own goals and methods of achieving them. One notable example is the artists’ colony at Worpswede, a small village near Bremen in Germany, founded in 1889 by artists such as Heinrich Vogeler and poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Worpswede garnered international attention, earning the moniker ‘Weltdorf’ (world village). In 1971, the colony received a new boost with the establishment of the Künstlerhäuser Worpswede (https://stätte.org/en), which has since evolved into a renowned residential art center.

In the 1960s, guest studios offered artists the opportunity to temporarily withdraw from what was perceived as bourgeois society, creating their own utopias in seclusion. Concurrently, residencies in cities and villages aimed to achieve social action, serving as bases for social and political change. This was evident in the Netherlands during the 1980s and 1990s with the rise of the squatters’ movement in larger cities. Artists seized vacant schools and factory buildings, claiming affordable living and working spaces. Over time, they developed programs and organized exchanges and presentations with colleagues through their international networks. Despite squatting being prohibited under new laws in 2010, its movement laid the groundwork for establishing a network of over 50 artist-in-residence programs across the Netherlands. These initiatives, predominantly organized by small, context-driven groups, are motivated by a strong conviction and vision of the arts, despite facing limited recognition and support from local governments and sponsors.

The punk counterculture movement La Movida emerged in Madrid during the 1980s, celebrating freedom, creativity, and expression after decades of dictatorship. This movement set the stage for a second wave of alternative art spaces in the 1990s. Artists, both in Spain and further afield, chose to organize themselves to face the challenges they were experiencing; a lack of art centers as well as the institutionalization of the role of the curator in the production of meaning and knowledge. Guest studio programs played a part in that alternative scene by finding ways to allow for diversity and productive disagreement.

Although the challenges artists face today have evolved, their methods of organizing remain similar. Artist-in-residence programs, beyond offering space and time for experimentation and serving as models of social and cultural exchange, can play a crucial role in revitalizing both rural and urban areas. This trend is particularly noticeable in rural Spain, where depopulation and climate change are pressing issues. Over the past decade, artists have settled into abandoned villages, exploring ways of working and living together. Others obtained old houses or farms and transformed them into independent programs. Now that landscapes are changing drastically due to the threat posed by severe droughts to local ecosystems and their habitability, more and more creatives and cultural spaces are creating strategies to make a positive impact.

Europe is home to a diversity of residency programs, shaped by various geographic, socio-political, and cultural factors. In the Netherlands, for instance, there are numerous small initiatives such as the experimental artist-run 1646 in the center of The Hague. In their art space, with attached guest studio, they welcome solo projects by artists who adopt strategies of fictioning, celebrate complexity or use humor to propose alternative points of view. They complement the more classical long-term studio programs and technical labs and facilities of the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, and the Jan van Eyck Academy in Maastricht. These residencies are formed in direct response to the position of art in society, influenced by factors such as funding and political trends. The profile of these programs is always in flux. Where small initiatives fade away, new ones emerge, with programs that reflect the societal developments of our time by increasingly engaging in pressing issues, from testing the limits of AI to questioning post-colonial narratives.

While many of these programs are independent spaces, operating on the fringes of the mainstream art scene, some wish not only to offer hospitality to artists but also serve as hubs for knowledge exchange and cultural innovation. Art centers like Rupert in Vilnius, Lithuania, play a vital role in connecting the local art scene with the global artistic community through exhibitions, talks, seminars, screenings and workshops. Their public program interconnects with guest studios and the Alternative Education Program (AEP), which aims to complement formal academic training and seeks a decentralized approach to knowledge sharing. This year’s thematic frame, “traversability and transgressions,” serves as a starting point for artists to further explore their practice. AEP provides curatorial guidance and a space where different practices and fields can meet—within or outside the field of art. With partner institutions and presentation venues both in Vilnius and France, Rupert offers an interesting platform for emerging artists and thinkers to start their career.

Functioning in a similar way is the International Cultural Laboratory in Sokołowsko, Poland. Deep in the thick forests of Central Europe, a tiny village and abandoned sanatorium has been transformed into lively creative enclaves. They include exhibition spaces, studios, an old cinema and the Sanatorium of Sound—a lab dedicated to experimental contemporary music and sound art. The former spa even houses the private archive of film scripts and correspondences of Polish filmmaker Krzysztof Kieślowski, who spent his childhood in the village. Residencies, events, and annual art, film and sound art festivals draw artists, writers, and musicians to the lab, especially during summer, when artists rent a room or camp out in the forest. Others settled in the area, enjoying the healthy air, low-cost life and tranquility ideally suited to writing or composing. Despite the current challenges in Poland in terms of support for contemporary culture, the drive and commitment of this grassroots initiative perseveres, slowly but steadily nurturing an international-minded community of artists and thinkers.

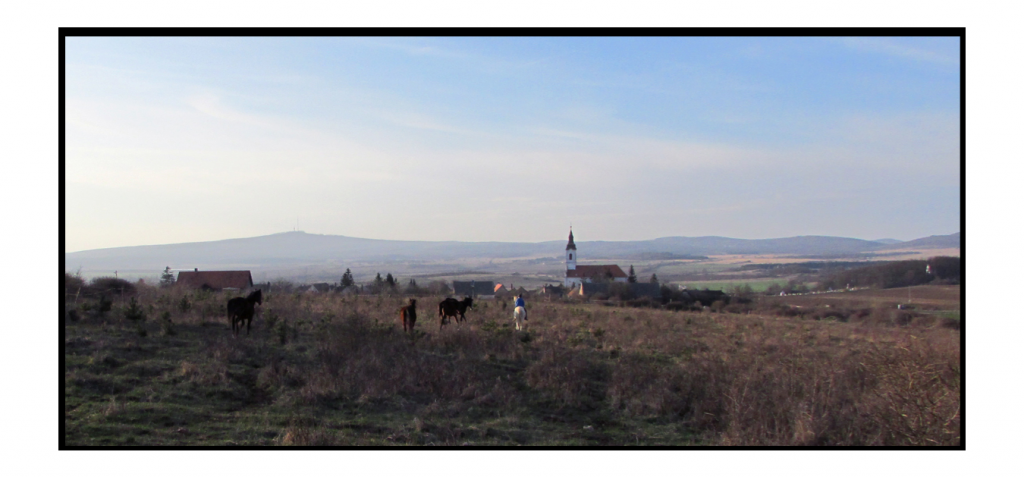

Embedded residencies are a rare and special type of program that offer conditions for art production in unexpected places. Think of lessons in horsemanship, anatomically correct riding and equestrian archery at the Horse and Art Research Program at a 19th century farm in Hungary. Here, artists and academics as well as riders interested in art engage with horse culture through daily practice, lectures and discussions. Serving as the entrance to a historic site, the Bridge Guard residency is located at the Mária Valéria bridge between Slovakia and Hungary. Before it was reopened in 2001, the bridge’s stubs kept the memory of the second World War alive for 57 years. To protect the rebuilt bridge from further destruction, an artist is appointed to make daily recorded observations of the bridge in the Bridge Log. “As long as the mental connection between people is intact, the bridge is not endangered,” reads the program description.

Horse and Art Research Program, photo from official site

Joya: Air, photo from official site

Typically, artist-in-residencies are the smaller players, yet they serve a key role in driving change from the ground up. Being well embedded in their contexts and professional networks, they can address local challenges that reflect broader issues in an increasingly complex society. Over the past few years in Europe, where conservative right-wing parties are gaining greater support, and where crises of climate, migration and the proximity of war are no longer an exception but rather a new reality, we saw how quickly artist-in-residence programs and the cultural sector in general can react and offer ad-hoc support to artists and cultural professionals who are forced to flee their countries. Others such as Joya: Air, an artist-run working farm situated in Andalucia in Spain, take on the role of stewardship amidst crises of climate and market-driven forces. Their field research center is dedicated to revitalizing the arid lands of the region. Here, artists work side by side with ecologists and environmental activists.

Zeus seduced Europa in the guise of a bull and abducted her from Tyre in Phoenicia (today’s Lebanon) to the Greek island of Crete. What if Europa decided to leave with the bull, simply because she wanted to travel and see another place?

At the 60th edition of the Venice Art Biennale, Lebanese artist Mounira Al Solh presents A Dance with her Myth. She reconsiders the origin myth of Europe from a feminist perspective, seen from the viewpoint of her side of the Mediterranean. In one painting, Europa stands harmoniously among young cattle, in another she carries a bull on her back. In another, her head is transformed into that of a bull, while she stands beside her suitcase ready for departure.

As you embark on your artistic journey through Europe, navigating the landscape of artist residencies, remember that diversity is at the heart of it all. Each program, from grassroots initiatives to established institutions, is embedded in the character, landscape, and focus of its region. No residency program is the same. It is therefore crucial to consider your artistic goals and preferences. What environment best supports your creative process? Do you crave a quick burst of inspiration or a longer, immersive experience? Do you thrive on collaboration or need focused time alone? By reflecting on these questions, you can narrow down your options and find a residency program aligned with your needs and aspirations.

Be adventurous, as Europa seems to suggest, and claim your narratives from your own viewpoint. Whether you are looking for exposure to international art scenes or a place for reflection and exploration of new directions in your art practice, engaging with colleagues and curators and encountering different critical perspectives can lead to fresh insights and reflections on your work. You may discover new materials and skills, experimenting with traditional weaving techniques during a workshop in Estonia or delving into programming at a hackers’ lab in Croatia. Residencies open doors to new perspectives, institutions, and networks that you might not find at home. Placing yourself in unfamiliar surroundings can be exciting and challenging; it stimulates you to push your artistic work forward and may potentially lead to lifelong networks of peers and friendships, in Europe and beyond.

Heidi Vogels has been the coordinator of TransArtists AIR NL since its beginning in 2003. AIR NL is a platform for the mutual exchange of information and experience between AIR organizations in the Netherlands and Flanders, connects AiR initiatives with (international) networks and platforms, and offers practical advice concerning AIR programs to art professionals, funders, and policymakers. She is also a visual artist and filmmaker.

TransArtists shares knowledge and experience about artist-in-residence opportunities for creative professionals through the website, workshops, research, and projects.

TransArtists is part of DutchCulture – Center for International Cooperation and is based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

2024.7.9Acasă la Hundorf Residency JournalArtist : Miyake Suzuko

2023.5.14AIR and I, 09 : Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art (MAWA) Residence Report